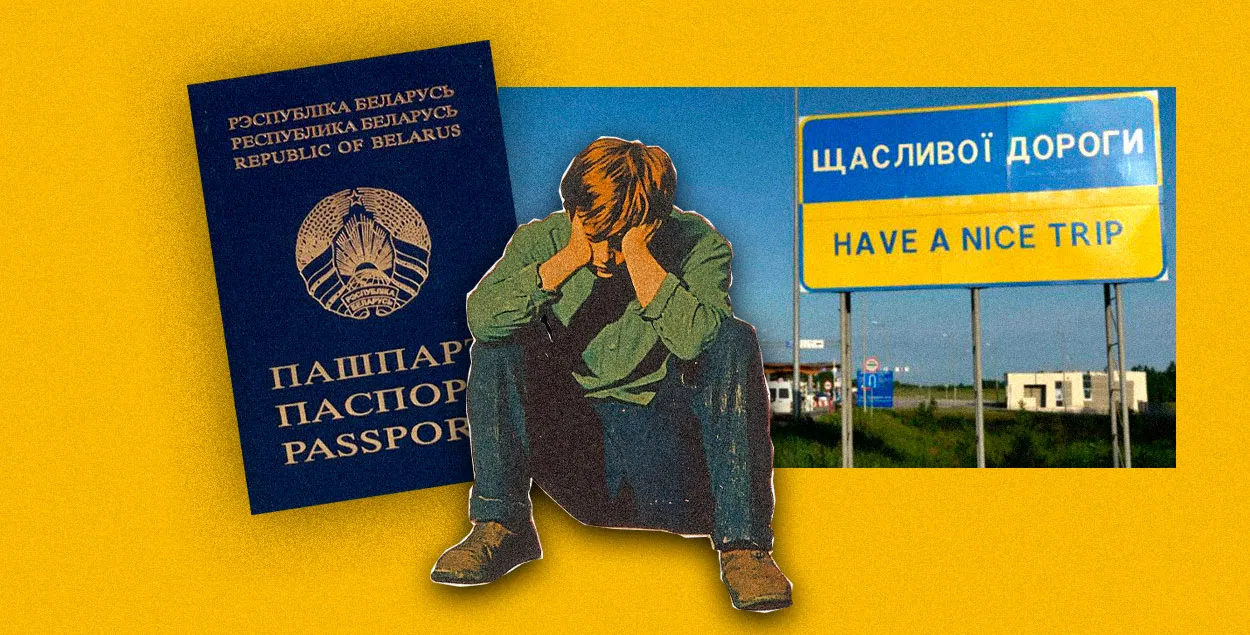

Why Belarusians struggle to legalise themselves in Ukraine

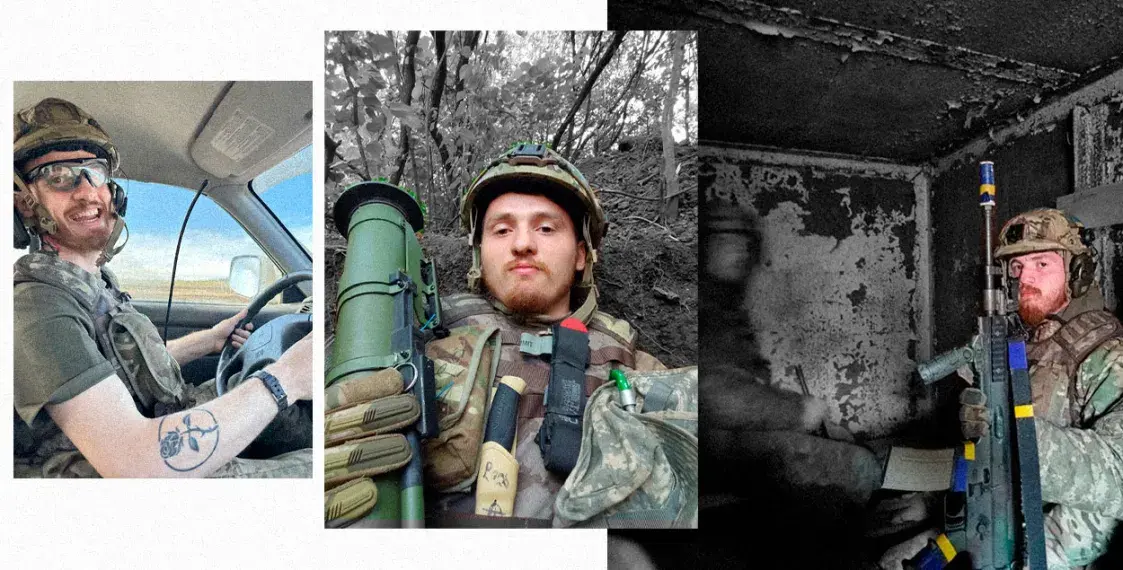

Even Belarusian volunteer fighters who defend Ukraine against Russian aggression are not spared from the bureaucratic maze. / @rubanau_collage

Human rights defenders warn that many Belarusians who chose to stay in Ukraine, despite the war, are now being forced to leave because of problems obtaining local documents. Among them are soldiers who fought on the front line, as well as civilians whose passports expired or were lost in the chaos of war. Without proper documents, legalisation becomes almost impossible.

Why Belarusians face such difficulties and what can be done – Euroradio and Graty investigate.

“I didn’t wait for a second chance for them to jail me”

“They throw you around like a football, and you are just an unfortunate Belarusian who wants to live his life,” says 34-year-old stylist Aleh Osipau, an asylum seeker who has battled Ukraine’s migration service for years.

Osipau fled Belarus in October 2020 after joining the protests against election fraud. Detained for 72 hours under the charge of mass riots, he was unexpectedly released. He went home, packed a backpack in fifteen minutes, and headed straight for Ukraine.

“They let me out of the temporary detention facility on Akrescina street in Minsk absolutely by accident. The next day, they realised and started calling. But I was already long gone. I didn’t wait for the second or third chance for them to jail me,” he recalls.

Without an EU visa in his passport, he headed to the first safe country – Ukraine. He stopped in Kharkiv, drawn by a friend and the city, which reminded him of his native Minsk. Although he considered moving on to Poland, financial difficulties and a sense of belonging kept him in Ukraine.

Aleh turned to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, as well as to the Polish consulate. The latter offered to issue him a visa, but for this, it was necessary to pay for insurance, which, Aleh says, he could not afford at the time.

With a temporary residence permit, Belarusians can legally live, work or study in Ukraine. However, this status offers only limited rights: it does not guarantee full access to banking, education, or healthcare services.

A permanent residence permit — effectively an immigration permit — is available under stricter conditions. It can be obtained, for example, by a spouse who has been married to a Ukrainian citizen for more than two years; by children or parents of Ukrainian citizens (including guardians and custodians); or by individuals whose spouses were killed while serving in Ukraine’s defence forces.

Additionally, the state may establish immigration quotas for specialists in science and culture, or for highly qualified professionals deemed essential to Ukraine’s economy. These provisions extend to their spouses and underage children, provided they relocate together. The same rules apply to foreign investors who contribute at least $100,000 in foreign currency to Ukraine’s economy.

In addition, foreigners – particularly Belarusians – who have faced persecution in their home country and risk torture or even death if returned, may apply for asylum in Ukraine. Yet, as the Free Belarus Centre points out, in recent years, only a handful of applicants have been granted this protection.

In the first months following Russia’s full-scale invasion, Aleh Osipau threw himself into volunteering. Working with the international charity foundation Sirius, he coordinated organisational tasks: securing donors, negotiating partnerships, overseeing shipments, and managing both the accounting and distribution of humanitarian aid.

But by October 2022, when Russian forces began targeting Ukraine’s energy infrastructure and blackouts became routine, burnout hit.

“I realised I was finished – I urgently needed to leave. I couldn’t give myself to people anymore. I lived and breathed this work, felt like I was saving the planet. So my boyfriend and I packed our things and went to the border,” Osipau recalls.

He was certain the border guards would let him through even without a passport, which had been taken when he applied for asylum — after all, he wasn’t a Ukrainian citizen. But they didn’t.

He returned to Kharkiv and once again turned to the migration service. There, he says, officials suggested he withdraw from the asylum procedure to reclaim his passport. But when his application was processed, Aleh was told the document had been destroyed in the Security Service building after a Russian missile strike on central Kharkiv on 2 March 2022. He was left with nothing –no passport, no legal status.

Armed only with a certificate confirming the loss of his passport, Aleh attempted to cross the border again. There, he recalls, he was met with hostility.

“So you thought you could come here, ask for asylum, we’d shelter you, and then as soon as things got tough you’d run straight off? Forget Europe. You’ll sit here now,’ the head of the border service told me. I left the crossing in tears. They didn’t let me say a word. I heard plenty about Belarus,” he says.

Until 2022, Belarus was considered a safe country

Human rights defenders note that the asylum procedure in Ukraine was already highly complex before the war – and it remains so today. Applicants must prove a risk of persecution in their country of origin. Previously, for Belarusians, even the initiation of a criminal case – for instance, for participating in the 2020 protests – was sufficient grounds for protection. Since the Russian invasion, however, grounds can now also include material support for Ukraine, which in Belarus may itself trigger criminal liability.

Yet even proof of money transfers in support of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, or screenshots from social media, is often dismissed by the State Migration Service (SMS) as insufficient.

According to lawyer Oleksii Skorbach, before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, Ukraine did not view Belarus as a country from which asylum could reasonably be sought. Even after the 2020 protests and mounting evidence of repression, the SMS continued to classify Belarus as a “democratic country with its specifics.”

“All the publications about the arbitrariness of the security services, the killings, the persecution of activists – none of it was taken into account. The courts upheld the migration service’s position, reasoning that while there were individual violations, they were not systematic or critical. Applicants were not deemed to be in real danger,” explains the human rights defender.

The situation worsened dramatically after 24 February 2022. As Skorbach notes, in the eyes of many Ukrainian institutions, Belarusians began to be automatically perceived as accomplices of Lukashenka’s regime.

Aleh versus the State Migration Service

After failing to leave Ukraine, Aleh returned to Kharkiv and re-applied for refugee status. The migration service turned him down.

He then took the matter to court. On 6 June 2023, the Kharkiv District Administrative Court ruled that the inaction of the regional office of the State Migration Service (SMS) was unlawful and ordered the agency to decide whether to accept Aleh Osipau’s refugee application. The appellate court upheld this decision.

Aleh re-entered the procedure, but in February 2024, his case was rejected again. The SMS dismissed his application as “obviously unfounded.” He filed another lawsuit.

Until August 2024, when the Verkhovna Rada finally amended the law “On the Legal Status of Foreigners and Stateless Persons Participating in the Defence of the Territorial Integrity and Inviolability of Ukraine,” Belarusian volunteers faced the same legalisation problems as civilians.

The amendment changed that. Foreigners and stateless persons defending Ukraine are now entitled “to obtain a temporary residence permit or immigrate, even if their documents have expired.”

For Emil, however, the struggle continues. Currently in the process of transferring to another unit, he had hoped to resign due to health problems, but was instead deemed fit for service. At the same time, he is trying to secure a Ukrainian residence permit. His only valid document is a Combatant’s Certificate: he surrendered his military ID when submitting his resignation request, and his passport was lost in Kramatorsk in 2023.

“I myself do not know what to do to stay in Ukraine legally,” Lobeiko admits. “Because in the State Migration Service, even though I have already been serving for more than three years, they said they cannot help at all, since I do not have a passport, and copies are not acceptable to them.”

He is now waiting for a copy of his contract to try again, this time at the SMS headquarters, where he hopes to apply either for a residence permit or asylum. Half-joking, Emil adds that without a passport, “at least they still won’t be able to kick me out of the country.”

The volunteer believes the real problem lies in Ukraine’s underdeveloped system for handling such cases.

“For example, I see that no one is interested in resolving legalisation issues — or maybe they simply don’t have the time. Even at my unit, the military command didn’t help with solving paperwork problems. I’m sure they didn’t even intend to: they don’t know these mechanisms and assume someone else deals with it,” he explains.

Meanwhile, in July 2025, President Volodymyr Zelenskyi signed into law a measure on multiple citizenship that, among other things, simplified the process of obtaining citizenship for foreign military volunteers. Instead of serving under contract for three years, they will now need to serve only one. Yet the law will not come into force until six months after its adoption – a delay that leaves volunteers like Emil still caught in limbo.

“To leave or fall outside the law”

One of the most pressing issues, says Free Belarus Centre head Palina Brodzik, is the narrow window for collecting documents after the end of labour or military contracts. Applicants have just three months to assemble a complete package of papers for a residence permit. Once this period expires, their legal stay in Ukraine will come to an end.

“To submit documents, you need to find a registered address with an owner willing to list you in their apartment. And only those with more than a year of continuous combat can obtain a residence permit — effectively three years of uninterrupted service, which in reality doesn’t happen,” he says.

Yavorskyi also points to a range of other obstacles Belarusians face in Ukraine: the near impossibility of opening bank accounts (many were frozen after 2022), limited access to insurance and notarial services, problems exchanging driver’s licences, difficulties registering marriages, and — since Ukraine suspended its agreement with Belarus in 2022 — the inability to recognise Belarusian educational diplomas.

“The recognition procedure is practically impossible to complete now, as the Belarusian Embassy in Ukraine is not functioning. Because of this, many doctors have already left for other countries,” Yavorskyi explains.

Separately, Brodzik highlights the institutional mindset within the SMS. While the agency treats Belarusians more neutrally than Russians, she says, “the overall impression is still that the presence of citizens from the neighbouring country is seen as undesirable.”

Against this backdrop, human rights defenders are increasingly advising Belarusians in Ukraine to consider leaving for EU countries, where legalisation procedures are clearer, and protection mechanisms are stronger.

This material was prepared in partnership with Graty, with support from n-ost and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.