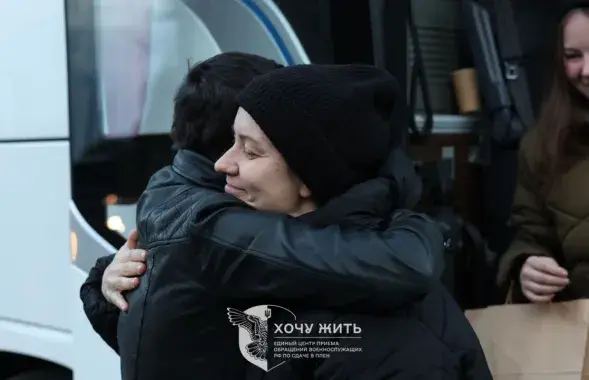

Mom returned from prison: the story of political prisoner Antanina Kanavalava

Antanina Kanavalava with her kids / Euroradio

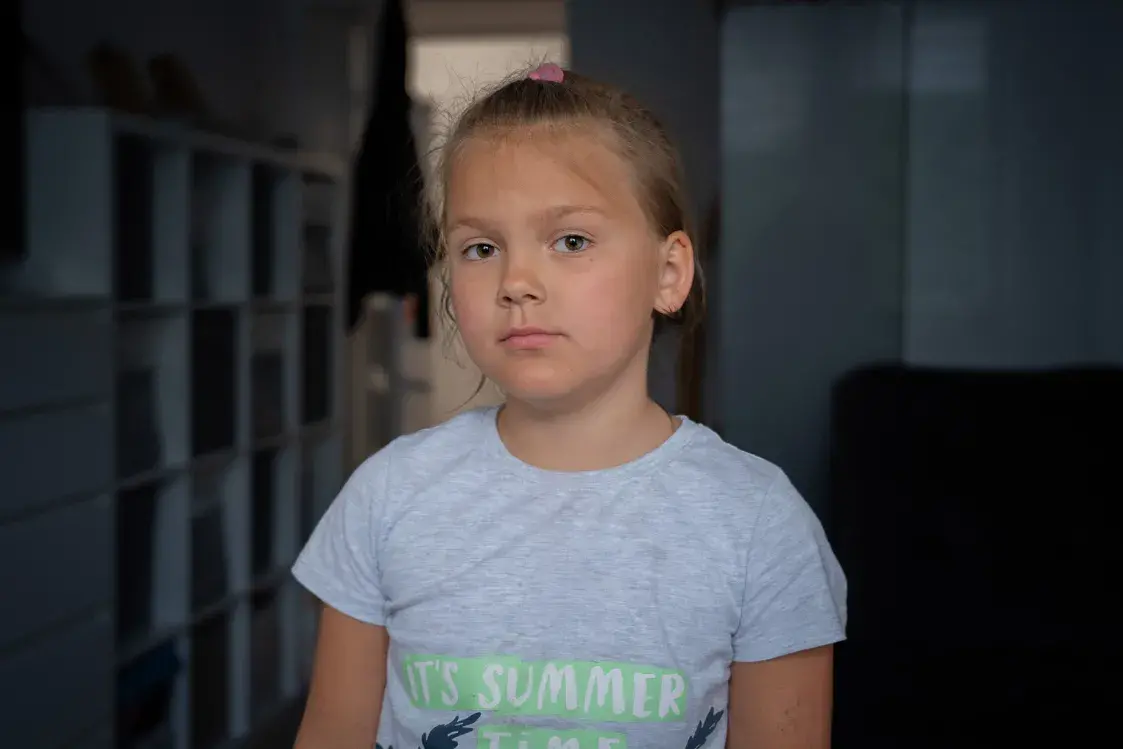

“At first I didn’t recognize who it was, but then, when mama came closer, I immediately knew and ran to hug her,” says eight-year-old Nastya. Until that moment, she hadn’t seen her mother for a long 4.5 years.

During the 2020 presidential election, Antanina Kanavalava was a trusted representative of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. In September 2020, Antanina—along with the father of her children, Siarhei Yarashevich—was detained. She was sentenced to 5.5 years for “preparation and participation in mass riots.”

In December of last year, Antanina Kanavalava was released from prison and recently reunited with her family. While she was in the penal colony, her mother took custody of two Belarusian boys. Now the Kanavalava family has also taken in two teenage girls who found themselves in a difficult situation in exile.

Kupalle

We meet Antanina during the celebration of Kupalle on the banks of the Vistula River in Warsaw. With a flower wreath on her head and surrounded by friends, she’s celebrating the summer solstice for the first time since her release from Women’s Correctional Colony No. 4 in Homiel. She chats with people and jumps over the bonfire — a traditional act symbolizing the casting away of evil and misfortune.

Antanina says she has no regrets:

“If I were told to go through this path again, I would. Maybe I wouldn’t have lost my children for four years — maybe I should’ve been a bit smarter, not so naïve. Unfortunately, I had to go through prison to understand that sometimes you need to put your naivety aside and take off the rose-colored glasses. That means I had to go through this path. And I told the girls not to regret anything: it means we were meant to meet here, it means we were meant to see each other, it means we were meant to go through all of this. So I can say that I am a happy person.”

Kids

Antanina, her mother Hanna, and the children live in a spacious social housing apartment in Warsaw’s Mokotów district. The apartment smells of fresh renovation. Anna received this two-room flat after a long period of wandering from shelters to friends’ homes with the kids. When Antanina was taken away by the security forces, Anna — late at night and with her young grandchildren — illegally crossed the border into Ukraine to protect them from being placed in foster care or an orphanage. Now, she can finally breathe a sigh of relief: her daughter is home, and they can share the burdens of everyday life together.

Antanina learned that two more children had joined the family while she was still in prison.

“Mom wrote that she just couldn’t walk past. And I understand — I would have done the same,” Antanina says about the first meeting. “When the three of them came to visit me (the oldest, Tsimur, couldn’t come because of school), I didn’t have enough arms. I felt like if I didn’t reach one of them, he’d be upset that I hadn’t hugged him tightly enough.”

Little Marsel also cried when he saw Antanina for the first time: “Mom came back,” he said. Two years ago, he and his brother joined Anna’s household. Their biological mother had been stripped of her parental rights. Not long after, she passed away.

Antanina sees how much her children have grown over the years — and how deeply politics has shaped their childhood. Nastya dreams of becoming the President of Poland (as well as a detective and a surgeon) and says that if she held such a position, she would never allow wars to happen.

“Vanya has really grown up. He remembers everything from start to finish — the armed men in masks who came to our home, how they sprayed them with a hose. And here and there, they remember crossing the border with grandma,” Antanina says about her son.

The children are helping Antanina recover. Nastya teaches her mother Polish and explains how artificial intelligence works. Vanya and Marsel show her the way to school and kindergarten.

Antanina quickly integrated into everyday life. Hanna now finds it much easier to share parenting duties. Especially since there has been a new addition to the Kanavalava family: they recently took in two Belarusian girls — Masha (14) and Alina (13). According to Antanina, the girls’ mother was stripped of her parental rights, but the Kanavalavas are doing everything they can to help the daughters reunite with her.

Not Yet Whole Family

The Kanavalava children still have one cherished dream — for their whole family to be together again. Antanina hasn’t seen their father (they divorced while she was in prison) for five years. Siarhei is still behind bars.

“I always try to find out how he’s doing. We weren’t allowed to correspond in prison. And I will never in my life say that the kids’ father is bad. He is a very good, wonderful dad. He raised them almost perfectly. Of course, it’s hard without a father figure. Vanya, as a boy, misses it. We go to the playground together, and there’s a dad playing football with his son — and Vanya wants that too. And for me, as a mother, it’s hard to watch from the side. He has no one to share his ‘guy secrets’ with, things he might not be able to tell me,” — at this point, Antanina can’t hold back her tears.

Nastya shows Euroradio her schoolwork. One drawing features a little hedgehog next to the flags of Belarus, Poland, and Ukraine — surrounded by slogans she’s heard many times at rallies she’s attended over the years with her grandmother and brother.

The second piece is a Father’s Day card:

“I love you and hug you tight.”

“I’m proud I’m raising children like this. They are much freer than I was. They are the generation that will return to Belarus and fight for freedom of speech,” says Antanina.

Minsk After Prison

Antanina admits that she never seriously considered emigrating from Belarus. At most, she thought about sending her children abroad to study.

“If they had let me live in peace there, it’s very possible I would have stayed and later brought my kids back. But our authorities didn’t leave me alone even after I was released. On the fourth day, I was already summoned by officers from GUBOPiK — so unfortunately, they left me no choice.”

Recently, Antanina applied to the Kalinowski Program — a scholarship initiative that helps repressed Belarusians access education in Poland. She plans to study English and later apply to a degree program in international relations.

“I’m not planning to leave politics. And I don’t think I will — not until all political prisoners are released. I’ll do my best to travel the world and tell people, through my own story, what it means to be imprisoned.”

Since being released, Antanina and several of her fellow former political prisoners have founded an initiative called Freedom Women, aimed at supporting women after their release from prison.

“We want to organize trips for girls to different countries so they can begin to recover — just lie by the sea for a week or see another country and forget the horrors they went through. We’ll be offering psychological and legal support. We also hope to open a small salon space, where each woman can feel beautiful again — do her hair, nails, and so on,” explains Antanina.

She calls her friends from prison her family.

“These are the people I went through everything with — from beginning to end: Darya Chultsova, Iryna Shchasnaya, Maria Kolenik. There was also a girl from Moldova, ‘not political,’ who supported me in prison for a long time. She even went with me to disciplinary commissions as a witness. She was released a year before me and later supported my parents. I saw in an interview that Dasha Chultsova said after her release that ‘this is more than family.’ And it’s true. There’s nothing like it. You know these people will never betray you and will always be with you.”

With support from The Exchange