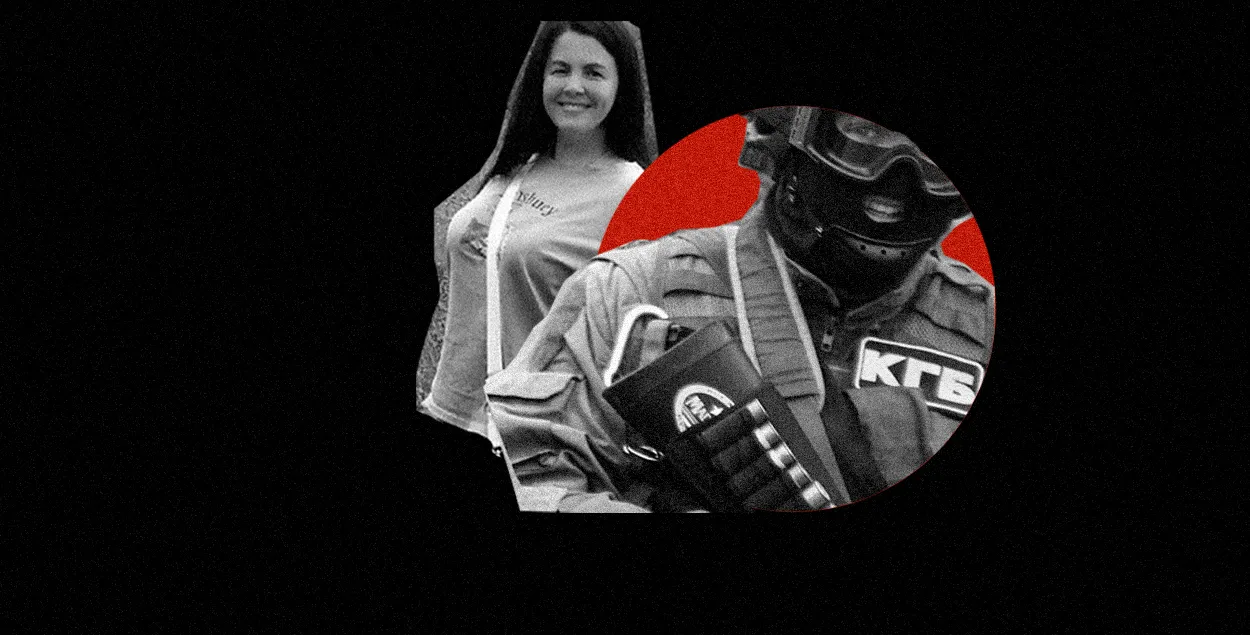

How a Ukrainian woman from Chernihiv became a political prisoner in Belarus

Natalia Yaroshenko / @rubanau_collage

At least 16 Ukrainian citizens are currently imprisoned in Belarus for political reasons. This figure, accurate as of 22 August, was provided by Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in response to a request from Graty and Euroradio. Ukrainians in Belarus are frequently accused of “agent activity”, espionage, and sabotage, or persecuted for taking part in the 2020–2021 protests.

Although Belarusian authorities usually allow Ukrainian consuls access to these detainees, they often fail to inform Kyiv of the arrests. As a result, the actual number of Ukrainian prisoners remains uncertain. The Belarusian human rights group Viasna has documented at least 15 such cases.

Human rights defenders report that seven Ukrainians have been convicted under the “agent activity” charges (Article 358-1 of the Criminal Code of Belarus), one under “espionage” (Article 358) and “organising and preparing actions grossly violating public order” (Part 5, Article 342), two under “mass riots” (Article 293), two for “public insult of the president” (Article 368), one for “violence against a police officer” (Article 364), and another under a combined charge of “terrorism” (Article 289) and “insulting the president” (Article 368).

At least one Ukrainian woman has been convicted of “assisting extremist activity” (Article 361-4). Under this article, Belarusians and foreigners alike have been prosecuted simply for passing information about Russian troop movements to Telegram channels. Some detainees have since been released.

Natalia Yaroshenko, a private entrepreneur from Chernihiv who worked in retail trade, spent almost five months without trial in a temporary detention centre in Homiel before being deported to Ukraine. Natalia was detained together with her sister, Lyudmila Honcharenko, who was later sentenced to three years for “agent activity” (Article 358-1 of the Criminal Code of Belarus). She was released in a prisoner exchange in June 2024. The Belarusian human rights centre Viasna recognised both sisters as political prisoners.

Here, Graty and Euroradio publish Natalia Yaroshenko’s monologue about her 147 days in Belarusian detention.

“They said they’d soon release me, but never explained why I was there.”

I used to visit Belarus often: we had many relatives there, and business connections. My sister’s first husband was Belarusian, from Homiel, and we had a relative living there as well.

When the war in Ukraine began, we travelled through Poland. And on one such trip, on 19 July 2023, I, my sister Lyudmila, and our sons, 13 and 14 years old, were detained.

We rented an apartment in Brest to spend the night and rest. In the evening, KGB officers knocked on our door and, without explanation, told us to pack our things.

Later, the children told us that when they went to the store, they saw those KGB men twisting the license plates on their car. They drove us to Homiel.

They explained nothing. I didn’t know why I had been detained. As many times as I asked both the head of the detention centre and the guards, they said they would soon release me home, but no one clearly explained why I was there. “You happened to be in the wrong place, at the wrong time.”

I admitted [to the investigator] that it was my voice, but neither I nor my sister realised that my nephew had been filming.

When I returned home while Lyuda was still there, the child was traumatised even more. I didn’t dare ask him about it. He was worried, thinking his mother would also be released. How can you tell a child it’s because of him? It’s a closed subject for us.

Our mother’s health also deteriorated. She was left with Lyuda’s three-month-old baby. For a long time, she didn’t know what happened to us.

During interrogations, they told me they had long wanted to take Lyuda. They knew we crossed the border. But at that time, she was pregnant. And one KGB officer told me: “We allowed her to give birth in Ukraine.”

“If things were bad, you wouldn’t be going home”

The KGB interrogated me frequently at first, then less. About 6–7 times. They told me I would undergo a polygraph test, and if the result were good, they would release me.

That day, they tormented me from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m. Interrogation at the KGB, then to the police for the polygraph, then back to the KGB. They never told me the results. Only when they drove me home did I ask, “Why didn’t you tell me the results?” “If things were bad, you wouldn’t be going home.”

At first, during interrogations, they said, “Nothing will happen to you, soon you’ll go home, be patient.” But when they opened a criminal case against Lyuda, they brought me to the investigator. He threatened me terribly — that I’d be an accomplice and get 10 years, that this was only a warm-up, that they’d arrest me again, and I should think about how I’d answer.

They also talked about the war, saying the president [Zelensky] was to blame, that “we work fairly here, not like in Ukraine with its corruption.” Of course, “the Americans are sponsoring the war — you’ll understand everything eventually.”

“I lost 18 kilograms during that time”

The conditions? Better not to ask.

When the KGB said I’d have to live in conditions “not as comfortable as I’m used to,” I thought, “Well, fine, I’ll manage.”

But when they brought me there and took away my bra, saying, “This is how you’ll walk here,” I had a breakdown.

At first, they put me with an alcoholic woman from Homiel. I stayed with her from Friday to Sunday. Then she was released, and I was sent to solitary confinement, a punishment cell without a window. No table, nothing — just a rough plank bed on high metal pipes and a grate.

I spent six days there. They didn’t give me books to read. I couldn’t tell if it was day or night. Then I became very unwell and started banging on the door. When the medic came and saw my condition, she ordered to send me to the medical unit.

My blood pressure was 180/120. The doctors claimed it was from smoking, but I don’t smoke.

They gave me a sedative, and I fell asleep. Later, I was moved to another small cell. Later still, when Lyuda was transferred to the pre-trial detention centre, they moved me to a cellmate from Ukraine who was awaiting deportation after losing her passport. We lived together in isolation for almost four months.

The place was infested with bedbugs. Sanitary services did the spraying, but it didn’t help. We were bitten badly. They gave us only one loratadine pill (for allergies) sometimes, but what is one pill?

No walks, showers once every 10 days, sometimes two weeks. I lost 18 kilograms, despite having a sedentary lifestyle.

Medical care was nonexistent. Only because I had some money with me could I ask the nurse to buy basic medicines. My sleep was terribly disturbed — I practically didn’t sleep, and fell into deep depression. Only then did they buy me sleeping pills.

When I returned to Chernihiv, I consulted a psychiatrist. He asked, “Who could prescribe you such psychotropics? That’s the strongest medication.”

We could “shop” inside only two or three times. Once they even offered me to buy them kettles for $100 in exchange for food. I agreed — I had to eat something.

“Yaroshenko, you don’t even look like a human anymore”

However, there were also people in the detention centre who helped: they gave advice, brought books, and talked with me.

One guard always cheered me up: “Yaroshenko, what do you want to eat? I’ll bring it from home. You don’t even look human anymore.” He only promised in words, but it was nice to hear him say it.

Sometimes, he let me shower earlier or change bed linen. Once, he even brought a razor! Small things, but in such an environment, they meant a lot.

Once, when there were no senior officers around, a guard let us walk in the yard for half an hour. But mostly, as they told me: “Do you know who you’re under here? Under the KGB. That’s your answer to all questions.” Even when I begged to be taken to the hospital for my leg, they said they had no right without “orders from above.”

Even when the Red Cross came with humanitarian aid for foreign citizens, I wasn’t on the list. A man just told me, “I feel sorry for you, I’ll give you something, but you’re not listed.”

“I looked at her, and she only mouthed words”

I was brought as a witness to Lyuda’s trial. A guard secretly told me to prepare for court — 7 December [2023].

I waited for that day as if it were salvation. They took me in the morning and warned that it would be behind closed doors.

In the courtroom, I saw Lyuda behind glass. She was skinny and visibly had high blood pressure. Later, at home, she told me she had collapsed and an ambulance was called.

Her face stuck with me — she just mouthed something, but I couldn’t understand.

Earlier, we had seen each other only once, during a face-to-face confrontation in October or November. I had been crying, annoying them, so they said, “If you stop crying, Lyuda will come and you’ll talk about home matters.” She told me then that the children had long been in Ukraine, and other news.

At court, the judge asked who she was to me. I said, “My sister”. They said I had the right to refuse testimony. And the woman near Lyuda mouthed “refuse”. So I refused.

I didn’t know if it was right or wrong. They wanted me to testify.

The judge looked past me and said, “The witness may leave.” I was not called again.

“There will be Lyuda’s verdict, and then we’ll decide”

I was released on 15 December [2023], two days before my birthday. The detention centre’s staff demanded I pay about $400 for my stay (21 BYN per day). I had almost nothing left, but my friend paid for it.

At 4 p.m., they took me to my friend’s place and said, ‘On 19 December, there will be Lyuda’s verdict, and then we’ll decide.’

After that, they came again in the morning, picked me up, twisted the plates on their car, put on masks, and drove me to the border. They erased my phone to factory settings, put a five-year entry ban on Belarus and Russia, and released me.

On the Ukrainian side, the SBU checked me, and by evening, my husband and children arrived.

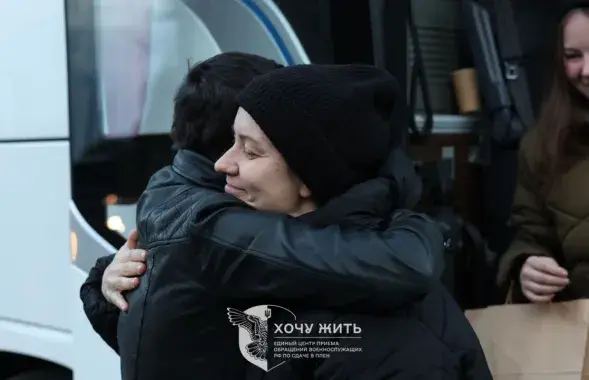

Half a year later, Lyudmila was exchanged.

“We thought she had been taken to Russia”

From the colony, Lyuda asked me, through the same friend, to send her children’s birth certificates. But the documents were returned with a note: “Lyudmila is not here.”

For a week, we didn’t know where she was. We thought she had been taken to Russia.

Then a friend called: “Did you see the news? Lyuda is already in Ukraine.” He sent me Zelensky’s post.

An hour later, she called me from an unknown number, asking me to tell our mother.

In the colony, Lyuda had a “yellow tag” — a mark identifying political prisoners. They were separated from others, sent to different jobs, fed differently, and treated under different rules.

I was always terrified of what was happening to prisoners in Belarus. Our cell was opposite the guard’s post, and we could hear how they beat people – dragging them out into the corridor, kicking. It was horrifying.

Ordinary prisoners could receive packages in their cells. Political prisoners had them taken away immediately. They were always led in handcuffs.

“Many people travel this way”

Chernihiv gets bombed. At the start of the war (meaning Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022), our house was destroyed, reduced to rubble. We barely survived. Our neighbourhood, Bobrovytsia, was in ruins — over 300 houses destroyed. Recently, there was another devastating strike.