Not Vilnius, Not Warsaw — Chernihiv: How the Americans liberated Belarusians

Belarusian political prisoners in Ukraine, 13 December 2025 / “Khochu zhit” / Хочу жить

My ideal picture looks like this: dozens of coaches cross into Poland or Lithuania; Belarusians line the roadside with flags and smiles, welcoming political prisoners into freedom the way Ukrainians greet their returning captives. But that is not how it happens with Belarusian prisoners.

This is how releases usually unfold – first, negotiations between Washington and Minsk (the latest round lasted 4 months). Then Donald Trump’s special envoy for Belarus, John Cole, travels to Minsk. State propaganda airs footage of his embraces and kisses with Alaksandr Lukashenka. After that, the American side announces another concession — this time, the lifting of restrictions on Belarusian potash.

“In accordance with President Trump’s instructions,” John Cole explained, “as relations between our countries are normalised, more sanctions will be lifted.”

Only then are political prisoners taken to the border. The truth is that, right up to the last moment, they do not know where they are being taken. But they can guess.

“I Was Taken Across the Entire Country Blindfolded”

“I was in the colony in Horki, in the Mahiliou region — right by the Russian border, 14 kilometres away. I was taken across Belarus from east to west, blindfolded. In that situation, there was not much of a choice: either remain in prison or be taken out like this. I am glad I am free,” said Ales Bialacki, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and human rights defender, serving a ten-year sentence for alleged smuggling and financing protests, in his first words after release.

John Cole brought Bialacki to Vilnius, together with eight foreign nationals released from Belarusian prisons. Vilnius was also expecting the remaining 114. Accommodation had been prepared for them, essential items had been purchased for the first days, and medical assistance had been arranged. Friends and relatives had arrived; acquaintances came as well.

Then, at the last moment, it emerged that the political prisoners had been handed over to Ukraine.

“I am not sure this was a step taken by the regime,” Ivan Krautsou — a representative of the team of Viktar Babaryka, who ran for president in 2020 — told Euroradio. “Perhaps the Lithuanian side refused to receive them. Or perhaps the Americans asked for this.”

Paper Bags, No Passports — and Accusations of Deportation

Viktar Babaryka, like his associate Maria Kalesnikava, and the campaign’s lawyer Maksim Znak, also ended up in Ukraine. They, like the others travelling with them, stepped onto “free ground” carrying the familiar paper bags — the same kind of parcels the regime “kindly” hands to Ukrainian prisoners swapped from Russian captivity, who are returned home along the same route via Nova Huta.

They were also without passports. This practice is widely used for people released with the help of the United States. Human rights defenders, politicians and former political prisoners themselves call it deportation. They also call it trafficking.

“Dear boys and girls, do you even understand what is happening? Can you not see that this is brazen, dirty human trafficking — encouraged by America, Europe, the whole world?” wrote Natallia Dulina, a former lecturer at the Minsk State Linguistic University and a former political prisoner. She was taken out of Belarus in the same way earlier this year, in June, alongside Siarhei Tsikhanouski.

Where Would They Be Taken — Vilnius or Warsaw?

For months, that question hung over journalists and political activists in exile, many of whom wanted at least some connection to the negotiations between Minsk and Washington.

Vilnius — because until now it had always been Vilnius. But relations between Lithuania and Belarus are at their most tense, not least because of cigarette-laden balloons crossing the border.

Warsaw — because Poland recently reopened two border crossings that had previously been closed, and appeared to hope that in return it might secure the release of Andrzej Poczobut, a journalist for Gazeta Wyborcza and a representative of Poland’s minority in Belarus.

Instead, it was Chernihiv. It was Ukraine.

“Kyrylo Budanov, the head of HUR, approached me,” Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy explained. “He said the Belarusians were ready to hand over political prisoners. They did not want to do it via one EU country or another, but if I supported it, they were ready to transfer them through Ukraine.”

However, the international relations analyst Roza Turarbekava is convinced that the decision to transfer Belarusian political prisoners to Ukraine was taken not only in Minsk, but also in Washington.

“I have always said that the Belarus–US track is not autonomous. It is an add-on to the negotiations about ending the war between Russia and Ukraine. Only in that context does Belarus come into the American administration’s focus. And Cole does not hide why he needs to talk with Lukashenka — because Lukashenka knows Putin well. But behind this lie other questions: border security and the security guarantees that can be provided to Ukraine through Lukashenka, because he controls Belarusian territory.”

First Steps in Freedom — and Questions About the War

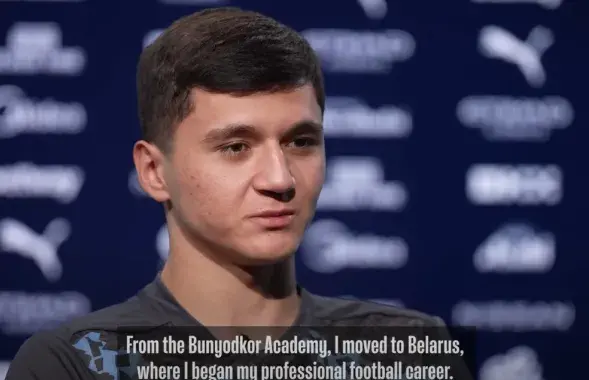

Ales Bialacki has already met his wife, Natallia. They even went to a shop and bought him a suit for a meeting with Lithuania’s President Gitanas Nausėda. Uladz Labkovich, Bialacki’s colleague from the Viasna Human Rights Centre, together with Babaryka, Kalesnikava and political strategist Alaksandr Fiaduta, held a press conference for Ukrainian media. The questions were predictable: about the war.

“I express full solidarity with Ukraine,” Labkovich said. “I have been in many detention facilities. In those places, 80 to 90 per cent of people wholeheartedly share Ukraine’s pain.”

During that discussion, Babaryka said he knew about the war only what he had seen on prison television. But by Monday, after a conversation with President Zelenskyy, his rhetoric sounded different.

“I am very grateful for the good words about Ukraine and Ukrainians, and for a clear, principled position regarding Russian aggression. This matters. Ukraine will continue to help everyone who helps us defend our independence and people’s lives,” Zelenskyy wrote afterwards.

A Call with the President of Ukraine

The conversation took place via video link. On the Belarusian side were Uladz Labkovich, Maksim Znak, the former editor-in-chief of TUT.by Maryna Zolotava, Maria Kalesnikava, Viktar Babaryka and Alaksandr Fiaduta.

Fiaduta was deported from a prison hospital, where he had been awaiting surgery. He walks with a cane and says he does not intend to return to politics — he wants to teach and write books.

Babaryka and Kalesnikava say they need time to take stock. In the meantime, they spoke with Lithuania’s Prime Minister Inga Ruginienė. They urged her to “give a chance to the diplomatic efforts of the United States, including on the release of political prisoners and the de-escalation of tensions between our countries”.

Whether Lithuania will agree to give the Lukashenka regime such a chance and reopen Klaipėda to the very potash for which the Americans have lifted sanctions in exchange for the release of 123 people remains a significant question. For now, Vilnius has said that the European Union does not plan to lift sanctions on Belarus.

Meanwhile, in the three days since the release, Belarusians have raised almost €250,000 for the former prisoners. A link to contribute is available here.

Produced with the support of the Russian Language News Exchange

Top of Form

Bottom of Form