‘My father said: ‘Come home’’: An Interview with a Venezuelan journalist

Gabriella, Venezuelan Journalist / фота з архіва суразмоўніцы Еўрарадыё

On Suturday, at 8 a.m. in Berlin and 2 a.m. in Caracas, Gabriella was woken by a call from her parents. They said they could hear explosions and that military aircraft were patrolling the sky over the city.

But Gabriella learned that Nicolás Maduro was no longer in the country earlier than her parents did. After the shelling, many neighbourhoods had no internet access. When she called home to tell them the news, her father shouted with joy, and her grandfather cried — happy tears. Gabriella spent the entire following day on the phone.

A Euroradio correspondent spoke with Gabriella shortly after Donald Trump’s press conference, when it became clear that democracy in Venezuela was still a long way off.

Gabriella explained to us how people inside the country are feeling now – and why their comments differ so sharply from those of political analysts. Explaining how years of repression shape how many Venezuelans understand the unfolding events and celebrate the overthrow of the dictator.

“The First Emotion Is Fear: Your City Is Being Bombed”

— How did you spend Saturday morning?

— My phone was exploding with messages. The first thing my dad noticed was the house moving, and he thought it was an earthquake. That's how he woke up and realised what was going on.

At eight in the morning, my father sent a video: shelling, helicopters circling above the city, explosions, people screaming. You could see people trying to evacuate the area around the main military base. By then, I had only just woken up and was trying to make sense of what was even happening.

The first feeling at that moment was overwhelming fear. All you see is your city being bombed. My entire family had gathered in Caracas at my parents’ house. Grandparents, uncles – everyone had driven 18 hours to spend the holidays together, so they were all home when it all happened. They were all sitting in the living room, praying and trying to make sense of what was happening.

That fear did not last long, because less than 2 hours later, I saw a tweet from Trump saying that they had taken Maduro out of the country.

A lot of friends wrote to me then: Is this true? Is this really happening? What could I say — it’s Trump, he can say anything. But I immediately called my family. There was no electricity in the city, and my relatives learned this news from me.

My father let out a cry of joy — it was pure joy. My grandfather started crying. It was a very emotional moment, especially for him: he is 80 years old and did not think he would live to see the end of the Maduro regime. And I, a thirty-year-old woman, have never known another government. The first thing my father said to me was: “You will finally be able to come home”.

I don’t think we would have seen this happening any other way. For more than 20 years, we went to protests, participated in elections—we used every possible method to change the regime and establish democracy in our country.

So it was pure joy and happiness. That’s how we felt at that moment. And then came the emotional roller coaster.

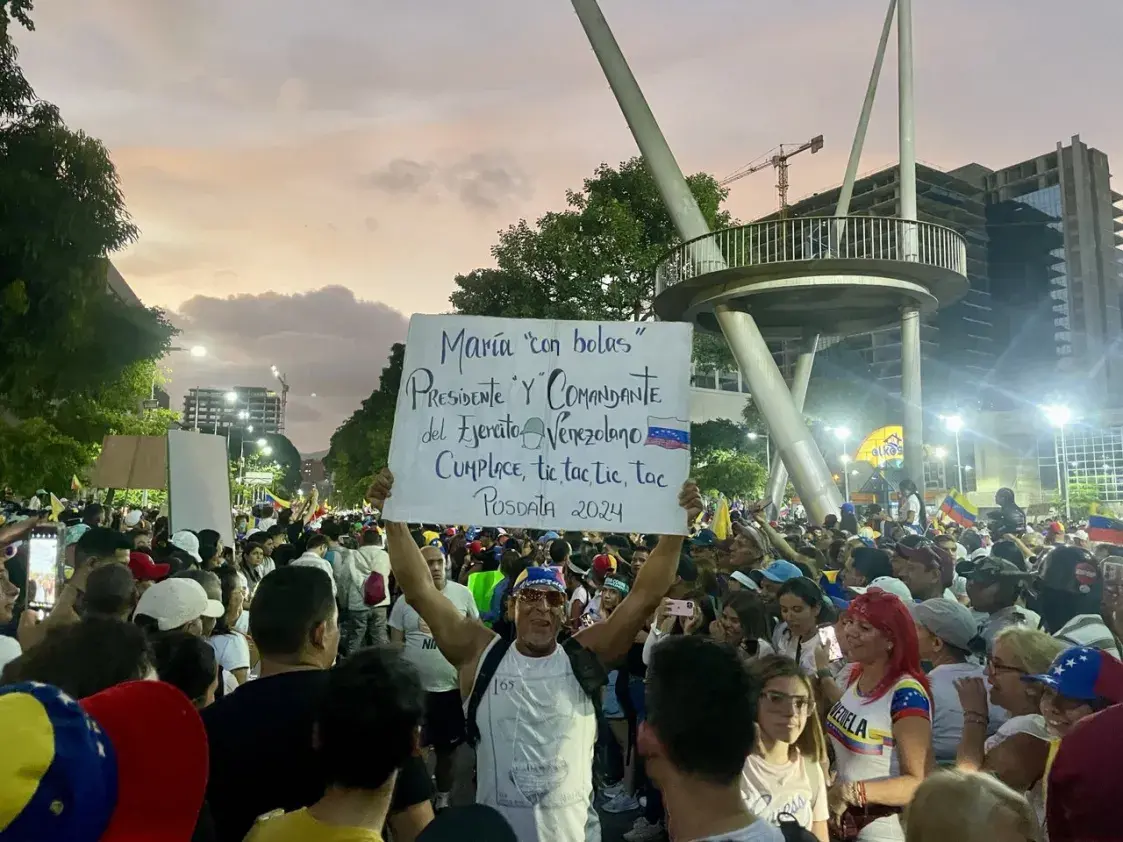

— You’re talking about Trump’s press conference, during which he said that Nobel laureate María Corina Machado “has no support or respect” among the Venezuelan people?

— That press conference was not what we expected. It left more questions than answers. The U.S. said it would manage the country. How exactly? For how long?

I expected the U.S. government to acknowledge that last year’s elections were fraudulent and to engage with María Corina Machado, a leading opposition figure, on how a transition of power might take place. That did not happen.

On the contrary, Trump said that the U.S. was negotiating with Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, who is part of this illegitimate regime.

Still, we have hope, because democratic change does not happen overnight. Yes, the events of last night prove that the U.S. can simply take a dictator out of the country — and out of his own home.

However, building an institutionalised democracy is a far more complex process, and the coming weeks will be critical in determining how events unfold.

“We Don’t Just Want to Remove Maduro, We Want to Change the Regime”

— What about Maduro’s supporters? Are they expressing their support for the ousted president in any way?

— I haven’t seen that. A small group of people voted for Maduro, but most of them were those who received government social benefits. They fear regime change, but even though I can’t provide exact figures, it's a small percentage of the population.

The majority of people in our country suffered under Maduro. There were years of food shortages, shortages of medicine, and years when children died in hospitals. More than 8 million people fled Venezuela, and the millions who stayed suffered from hunger.

For a democratic transition of power, a certain order must be established. Of course, we would have liked to hear [from Trump — Euroradio] that Edmundo González, the legitimately elected president in the 2024 elections, would take power. But that did not happen.

Nevertheless, the U.S. government wants to change the people in power. I don’t think all of their actions are driven solely by interest in Venezuelan oil. Because if it were only about oil, they wouldn’t need to put Maduro on trial – he was making open offers to the U.S. I hope we simply don’t know about large-scale non-public negotiations.

The international audience says: everything that happened was illegal. Yes, it was unlawful. But Maduro’s government is also unlawful. Stealing elections is illegal. And the international audience must hear that. This is not about whether you support right-wing or left-wing ideology – the Venezuelan case goes beyond right and left views.

— Do you think the reward promised by Trump for information on Maduro’s whereabouts helped make this operation possible?

— Oh, there were so many jokes about this on social media. That reward started at 15 million and rose to 50 million dollars.

During the press conference, Trump addressed the bounty with a joke, telling people not to come asking for the money. The implication was that the operation was carried out entirely by the United States, without outside assistance.

But public statements – particularly off-the-cuff remarks – do not always provide a complete or reliable account of how such operations unfold.

Several alternative explanations have circulated. One persistent theory suggests that someone within Maduro’s inner circle provided U.S. authorities with detailed intelligence, enabling the American military to locate him. Since November, multiple reports have indicated that Maduro had been changing locations daily and sleeping in different residences to avoid detection. Despite these precautions, U.S. forces reportedly located him with relative ease, leading some observers to believe that someone from within his own network had shared precise, real-time information.

“Does America Only Want Oil? This Government Also Only Wanted Oil”

— Let’s talk a bit about Venezuela for those who only started following events in your country on Saturday morning. Even they know that Venezuela is rich in oil. So why is the economic situation so dire?

— The short answer: resource revenues never reached ordinary people. They went into the pockets of those in power, people from the Maduro regime, into private bank accounts of family members and friends of those connected to the government. Then oil prices fell, and, combined with poor management, that led to a crisis.

Many observers have argued that the US interest in Venezuela has focused mainly on oil. That is partly true – oil has always been a central factor in the country's international engagement. But it is essential to recognise that, for decades, the Venezuelan government itself prioritised control over oil and other strategic resources over the welfare of ordinary citizens.